ANALYTICAL SPECTROSCOPY

by Raymond P. W. Scott

D.Sc., F.R.S.C., C.Chem., C.Sci. F.A.I.C, F.C.S.

Essential Information for the Analytical Chemist

Specialising in custom-designed, precision scientific instruments, built, programmed and calibrated

to the most exacting standards. The range includes precision dataloging barographs,

with built-in statistical analysis, Barographic Transient Event Recorders

and computer-interfaced detectors and sensors

for environmental monitoring & process control.

A site dedicated to scientific techniques, experimental methods, &

investigative tools for the inventor, researcher

and laboratory pioneer. Articles on glassblowing, electronics, metalcasting, magnetic

measurements with new material added continually. Check it out!

www.drkfs.net

Experimental Fluorescence Spectroscopy

The

sample cells used for fluorometric measurements must be constructed

of materials that are transparent to the wavelength of light being

measured. Even very pure materials may still have traces of

fluorescent contaminants and new or replacement cells should always

be examined for background Fluorescence. Cells and other glassware

employed in fluorescent measurements should be well cleaned and

preferably boiled in 50% nitric acid solution followed by careful

rinsing with distilled water. Any solvents employed must be checked

for background Fluorescence; if inherent Fluorescence is found

present in a solvent it can often be removed by distillation. If

water is to be used as the solvent it should be deionized distilled

water. Plastic containers should be assiduously avoided as trace

florescent materials can be leached from the plastic by any solvents

stored in them. High quality solvents should always be used and blank

fluorescent measurements taken before use. Although commonly used for

cleaning glass apparatus, commercial detergents should be avoided, as

some are strongly fluorescent; if detergents are used, then their

fluorescent properties should be evaluated prior to use. Fluorescent

contaminants can arise from stopcock grease, filter paper and from

micro organisms developing over time in buffer solutions. Dilute

solutions are basically unstable and should be prepared immediately

prior to use from strong standard solutions that may be stored with

some confidence over extended periods of time. The surface of glass

and other types of containers can absorb substances onto their

surface and if the concentration of those substances is very small,

adsorption can remove a significant amount of the analyte from

solution and impair the accuracy of any measurement. For example

glass surfaces have strongly polar interactive sites and if an

aromatic hydrocarbon dissolved at very low concentrations in a

dispersive solvent (e.g.

n-heptane,

or petroleum ether ) is stored in a glass bottle, the glass surface

will become saturated with adsorbed aromatic hyrdrocarbon. Thus, its

concentration in the dispersive solvent will be significantly reduced

and any analysis of the solution will give low results. Under certain

circumstances the intensity of the excitation light can cause analyte

decomposition. This effect can be reduced employing an appropriate

shutter between the light source and the sample cell and this shutter

is only opened for a short time during measurement. Better

alternatives are to identify a wavelength for the excitation light

that does not cause sample decomposition or reduce the excitation

light intensity by using a narrower slit. Finally, the presence of

oxidising agents (e.g.

dissolved oxygen or the presence of peroxides ) may initiate a

reaction with the Fluorescence substance and consequently reduce the

Fluorescence. Care must be taken to ensure such oxidising agents are

absent from the sample.

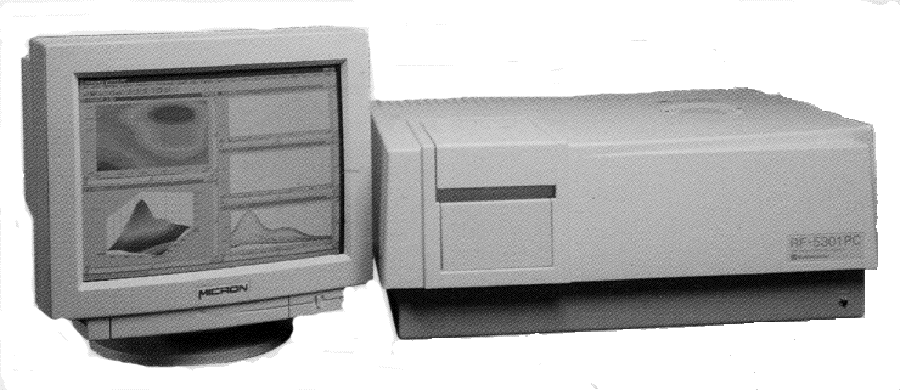

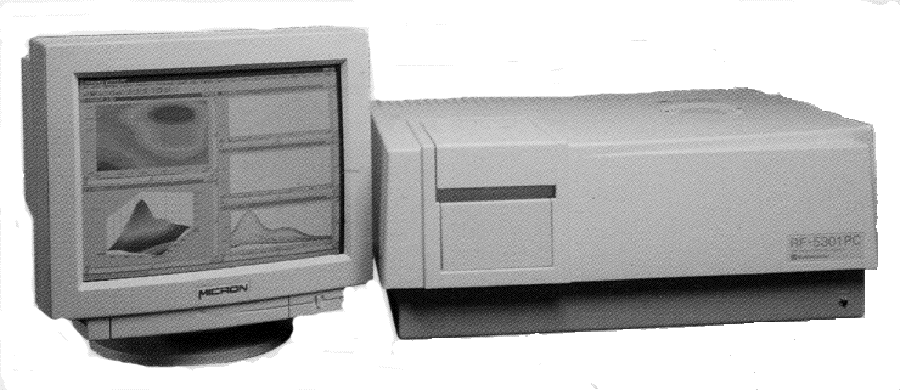

A typical example of a

Fluorescence spectrometer is that manufactured by SHIMADZU for

routine research and routine analytical purposes and is shown in

figure 11. The compact, high sensitivity model of this range can

handle extremely small samples and easily detect and determine trace

concentrations of pollutants. Capillary cells having volumes of 5 μl

or less are also available.

.

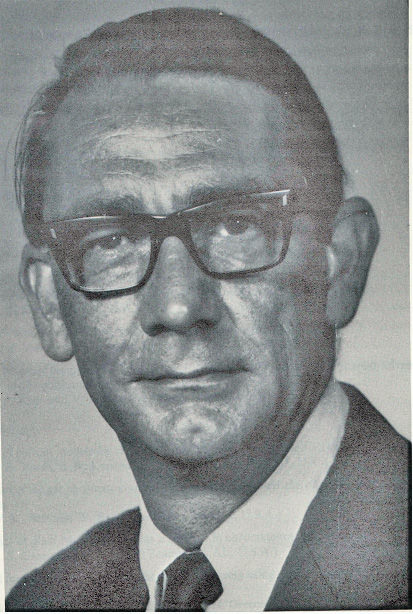

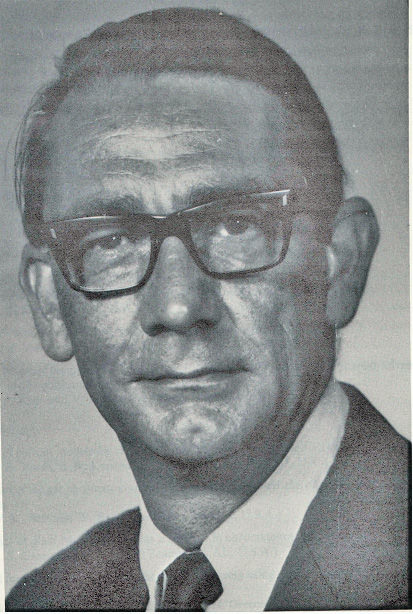

About the Author

RAYMOND PETER WILLIAM SCOTT was born on June 20 1924 in Erith, Kent, UK. He studied at the

University of London, obtaining his B.Sc. degree in 1946 and his D.Sc. degree in 1960.

After spending more than a decade at Benzole Producers, Ltd. Where he became head of

the Physical Chemistry Laboratory, he moved to Unilever Research Laboratories as

Manager of their Physical Chemistry department. In 1969 he became Director of Physical

Chemistry at Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ, U.S.A. and subsequently accepted the position

of Director of the Applied Research Department at the Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Norwalk, CT, U.S.A.

In 1986 he became an independent consultant and was appointed Visiting Professor at Georgetown

University, Washington, DC, U.S.A. and at Berkbeck College of the University of London; in 1986

he retired but continues to write technical books dealing with various aspects of physical chemistry

and physical chemical techniques. Dr. Scott has authored or co-authored over 200 peer reviewed

scientific papers and authored, co-authored or edited over thirty books on various aspects of

physical and analytical chemistry. Dr. Scott was a founding member of the British chromatography

Society and received the American Chemical society Award in chromatography (1977), the

M. S. Tswett chromatography Medal (1978), the Tswett chromatography Medal U.S.S.R., (1979),

the A. J. P. Martin chromatography Award (1982) and the Royal Society of Chemistry Award in

Analysis and Instrumentation (1988).

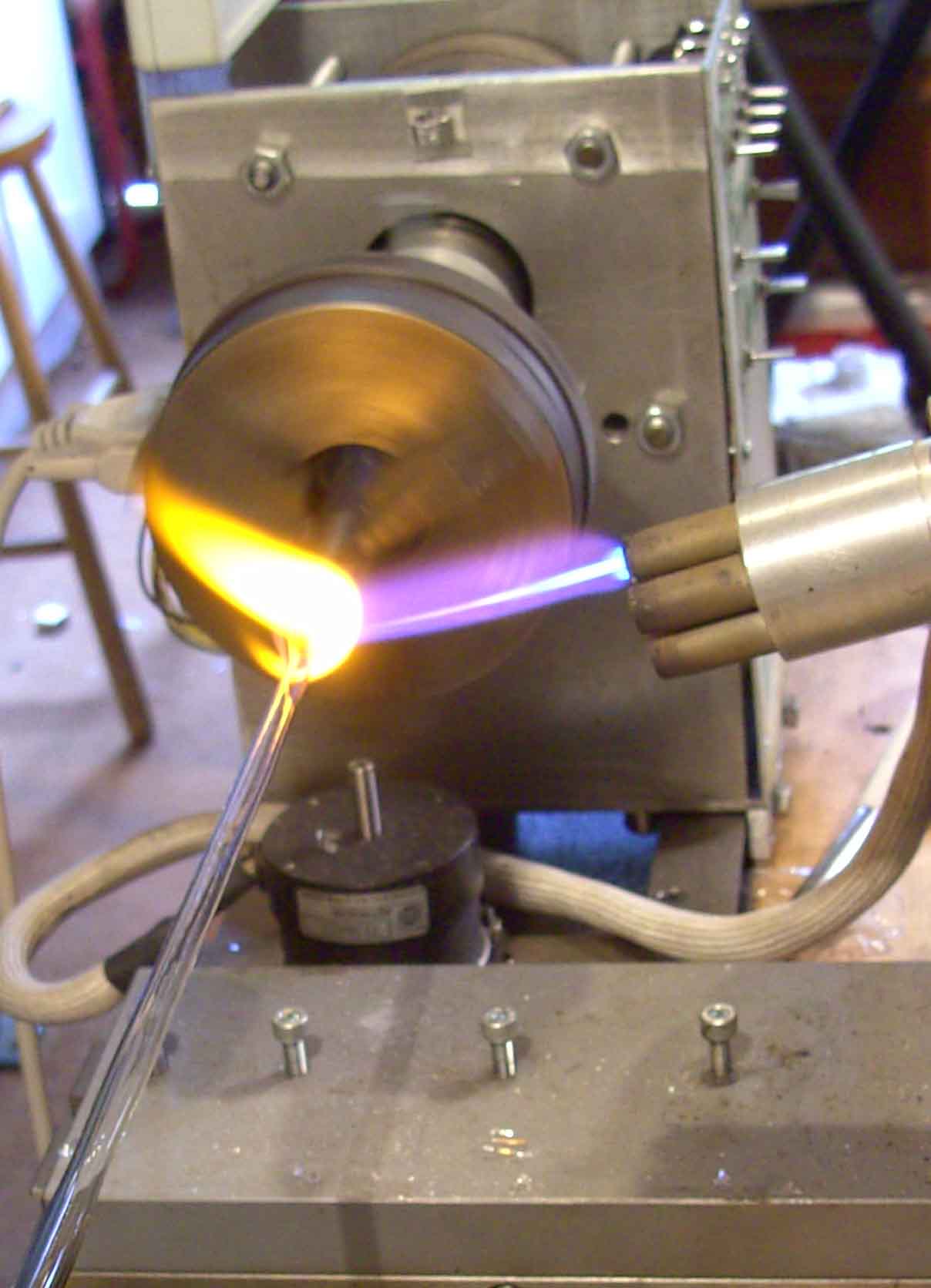

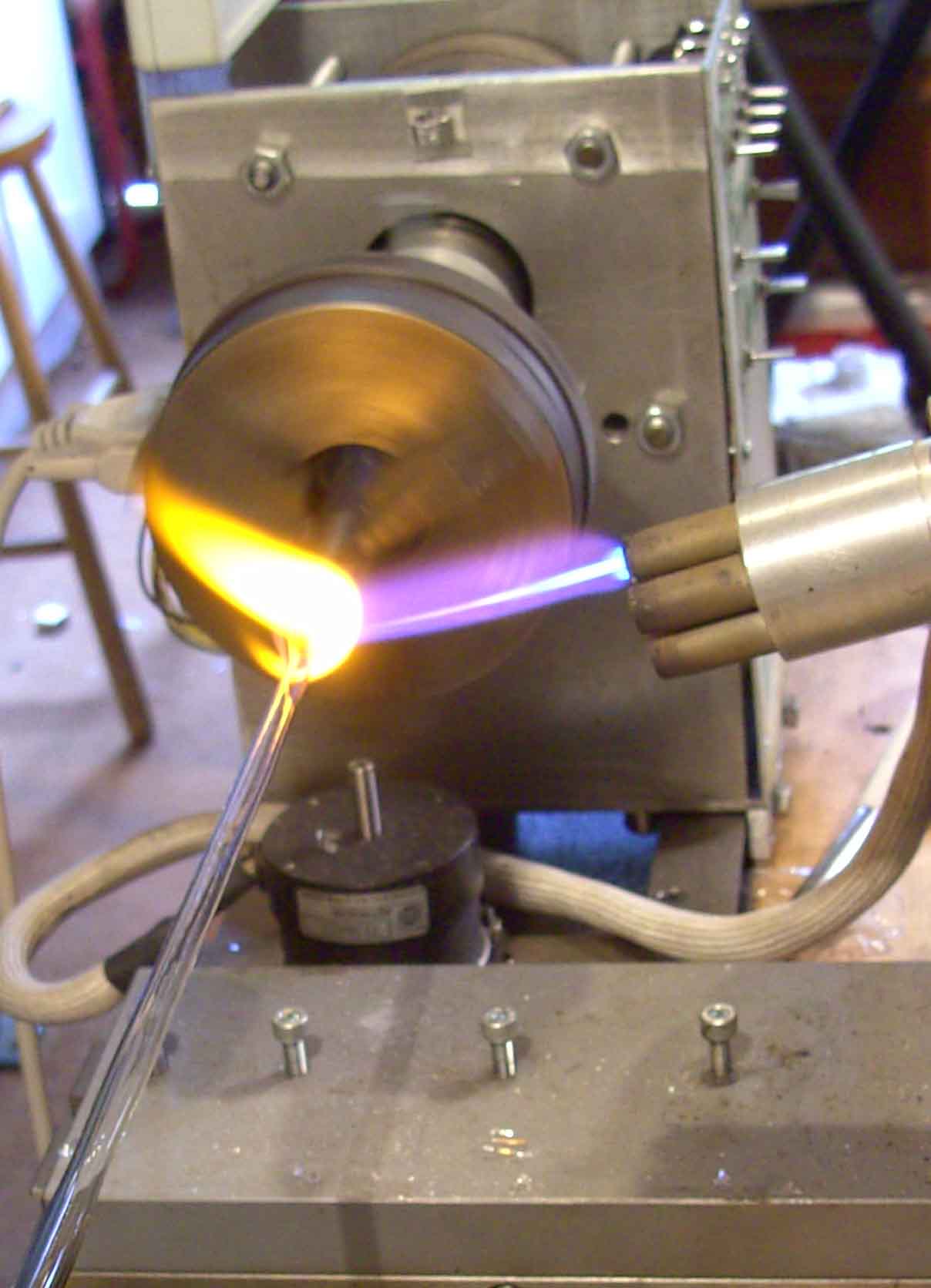

Dr. Scott’s activities in gas chromatography started at the inception of the technique,

inventing the Heat of Combustion Detector (the precursor of the Flame Ionization Detector),

pioneered work on high sensitivity detectors, high efficiency columns and presented fundamental

treatments of the relationship between the theory and practice of the technique.

He established the viability of the moving bed continuous preparative gas chromatography,

examined both theoretically and experimentally those factors that controlled dispersion

in packed beds and helped establish the gas chromatograph as a process monitoring instrument.

Dr. Scott took and active part in the renaissance of liquid chromatography,

was involved in the development of high performance liquid chromatography and invented

the wire transport detector. He invented the liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

transport interface, introduced micro-bore liquid chromatography columns and used them

to provide columns of 750,000 theoretical plates and liquid chromatography separations

in less than a second.

Dr. Scott has always been a “hands-on” scientist with a remarkable record of accomplishments in chromatography ranging from hardware design to the development of fundamental theory. He has never shied away from questioning “conventional wisdom” and his original approach to problems has often produced significant breakthroughs.